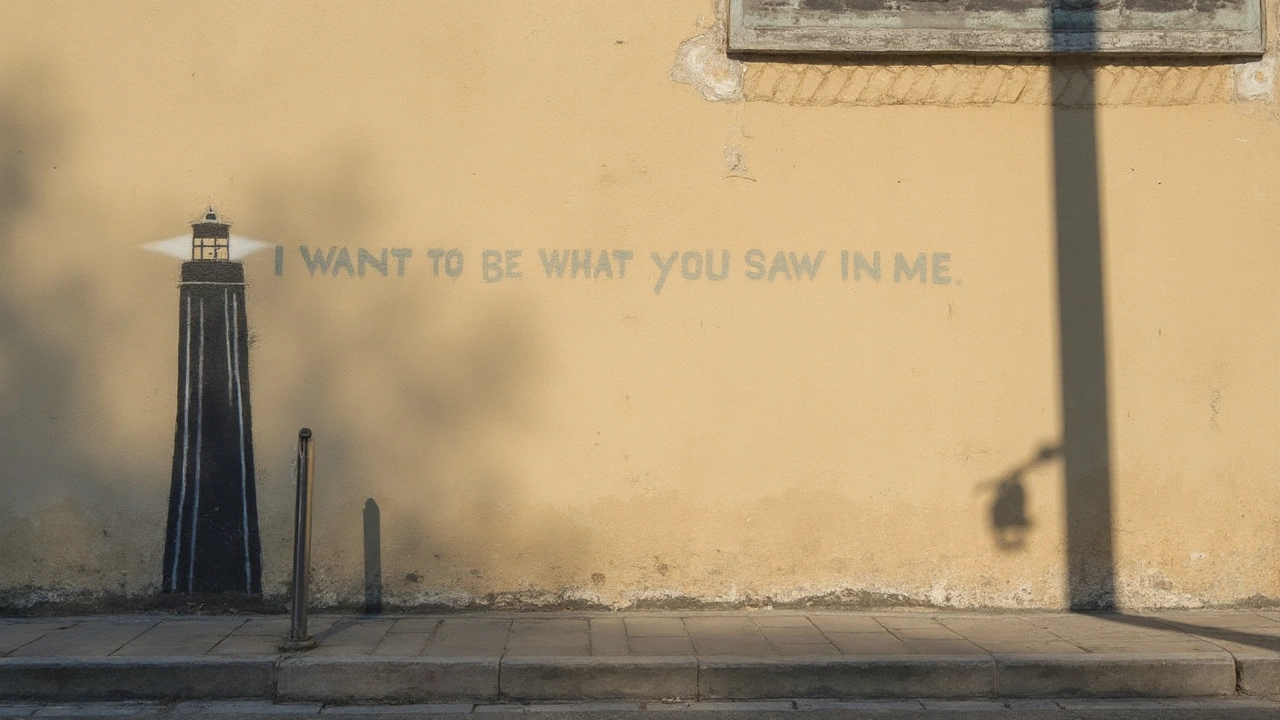

Banksy Mural at Royal Courts of Justice Removed Within Hours Amid Palestine Action Crackdown

A judge, a gavel, and a wall that went dark

Banksy picked one of Britain’s most powerful addresses for his latest hit-and-run mural—and it disappeared almost as fast as it arrived. Early Monday, September 8, 2025, a painting appeared on an outer wall of the Royal Courts of Justice in Westminster. It showed a judge in robes and a towering wig swinging a gavel at a protester, blood splashing across the demonstrator’s placard. Within hours, the wall was wrapped in black plastic, fenced off with metal barriers, and placed under guard.

The timing and imagery were not subtle. The piece landed days after London saw a wave of arrests—nearly 900 in total—at a rally sparked by the government’s decision to proscribe Palestine Action as a terrorist organization. Organizers put attendance at around 1,500 and insist the gathering was peaceful. The Met’s arrest tally indicates more than half of those present ended up in custody.

The mural was placed on the Queen’s Building, part of the Royal Courts complex. A security camera above the scene had been turned away, an odd detail that immediately fed the reading that the work was a jab at surveillance, accountability, and the state’s grip on public space. Banksy posted images on Instagram and his website, captioned with a simple locator: “Royal Courts of Justice. London.”

By mid-morning, the state had moved to reclaim the wall. A spokesperson for HM Courts and Tribunals Service (HMCTS) said the artwork would be removed to maintain the listed building’s original character: “The Royal Courts of Justice is a listed building and HMCTS are obliged to maintain its original character.” The speed spoke for itself—this was not going to be one of those murals that a council fences off and adopts.

The Metropolitan Police confirmed they are treating the painting as criminal damage. That matters for more than the expected cleanup bill. A criminal case could test the edge of the artist’s long-guarded anonymity, which has held since the mid-1990s despite countless rumors. If prosecutors ever brought charges, the question of identity would move from gossip to a legal problem.

Art aimed at power—and a political fight in the streets

The subject of the mural was always going to be read against the crackdown on Palestine Action and the arrests at the rally that followed. The group, founded in July 2020, was proscribed by the Home Office in early July after activists broke into RAF Brize Norton in Oxfordshire and sprayed two military planes with red paint. Then–home secretary Yvette Cooper signed off on the decision. Under the proscription, membership is now a crime punishable by up to 14 years in prison.

Defend Our Juries, which supports Palestine Action, called the mural a warning shot at the system that criminalized the group. A spokesperson said the work “powerfully depicts the brutality unleashed by Yvette Cooper on protesters by proscribing Palestine Action,” using the word “dystopian” to describe the ban.

Art market analyst Jasper Tordoff from MyArtBroker focused on the staging as much as the image. “What makes this work remarkable is not just its imagery, but its placement,” he said. “By choosing the Royal Courts of Justice, Banksy transforms a historic symbol of authority into a platform for debate. In classic Banksy form, he uses the building itself to sharpen the message, turning its weight and history into part of the artwork.”

That location does a lot of heavy lifting. The Royal Courts of Justice houses the Court of Appeal and the High Court. It is literally where the state decides what counts as lawful protest, where free expression meets public order, and where government power is tested. Putting the mural under a turned-away camera underlines the argument: institutions look the other way until force is used, and then the hammer comes down. Whether you agree with that framing or not, the building makes the critique feel immediate.

The sequence was stark. First the appearance. Then the claim of authorship via Instagram. Then a rapid cordon by officials and a clear statement that the work would not be allowed to remain on a protected façade. All of this played out against a backdrop of heightened policing of protest since new public order powers came into force in recent years. The friction point is familiar: is this free expression or illegal defacement, legitimate protest or unlawful disruption?

For the courts, the answer is straightforward. This wall is part of a listed building. Any alteration—spray paint included—is not just graffiti, it’s damage to a protected structure. HMCTS’s duty is to preserve, not curate. For the artist’s fans, the speed of the blackout reads as proof that the message hit a nerve.

Here’s what we know so far:

- When: Early Monday, September 8, 2025; covered and cordoned within hours.

- Where: External wall of the Queen’s Building, Royal Courts of Justice, Westminster.

- What it showed: A judge beating a protester with a gavel, with blood across the placard.

- Why it matters: Arrived amid mass arrests linked to the proscription of Palestine Action.

- Police response: The Met opened a criminal damage investigation.

- Official stance: HMCTS says the work will be removed to protect the listed building.

The political context is doing as much work as the paint. Proscribing a group triggers some of the heaviest criminal penalties available short of violent offenses. When that decision is followed by mass arrests at a demonstration, any art placed on the courts’ doorstep is going to be read as a verdict on the state’s threshold for dissent. The gavel in the mural is not about a courtroom nicety; it’s about a blunt instrument.

Palestine Action’s tactics—direct action and symbolic damage—have always attracted strong reactions. The RAF Brize Norton incident, in which activists sprayed two planes with red paint, helped tip the balance inside government. Supporters say these are targeted interventions meant to expose Britain’s role in overseas conflicts. Critics see a pattern of criminal damage dressed up as activism. The proscription decision hardened that divide and immediately raised the stakes for anyone seen to support the group.

Visuals like this spread fast because they compress arguments. One painted swing of a gavel suggests courts backing force over debate. A turned-away camera implies the public is observed until authority acts, at which point the lens looks elsewhere. The location communicates that the rule of law is not an abstract idea; it’s a building, with walls that can be marked and scrubbed clean.

What happens to the artwork now? If the wall is listed, specialist contractors will typically remove paint with methods that don’t damage the stone, monitored by conservation staff. Because the police consider it criminal damage, any fragments or materials could be kept as evidence. There’s no sign HMCTS will preserve the image on-site or send it to storage. When the state says “remove,” the default is removal, not conservation or sale.

There’s also the market myth to clear up. Street pieces rarely make it to auction without heavy controversy. Even when a section of wall is cut out, questions of ownership and permission are messy. Here, the property belongs to the courts. The government is not in the business of slicing up Grade I–style stonework to cash in on a mural, especially one it just called damage.

Then there’s the artist’s anonymity. Police investigations won’t necessarily unmask him. Banksy’s projects usually involve small crews, night work, and minimal traceable supply chains. Even if officers identify helpers, that does not automatically lead to the artist. In past cases, the name has stayed off the charge sheet because the evidence didn’t cross the threshold. But each high-profile work adds pressure. If a case did reach court, defense and disclosure rules could drag that private identity into a very public room.

The bigger point is how this plays with the public. Some will see an attack on a national institution and shrug—clean it off. Others will see a blunt warning about the cost of protest in today’s Britain. The courts sit in the middle, charged with drawing lines between expressive acts and criminal ones. Put the debate right on their wall and you force that conversation for a day, even if the paint is gone by night.

None of this is new terrain for the artist. Banksy’s career has been one long argument about who gets to speak in public space. From early Bristol stencils to global pieces tackling war, migration, and surveillance, he’s used quick, high-impact images that people grasp in seconds. The content swings between deadpan humor and bleak irony, but the targets are usually the same: power, money, and the systems that protect both.

He also knows how to set a stage. Think about the auction-room stunt when a work self-destructed as the gavel fell, or earlier pieces that landed on sensitive sites to question policing and privacy. The method is always similar: pick a loaded surface, deliver a simple picture with a hard edge, and let the internet do the rest. Here, the loaded surface is about as loaded as it gets—the building that symbolizes legal authority in England and Wales.

On the ground, the practical aftermath is dull but decisive. Security cordons, conservation advice, cleaning schedules. HMCTS will likely move fast to return the wall to its pre-mural state. The Met will collect statements, review footage, and track materials where they can. If anything substantive turns up, we’ll hear about arrests or charges. If not, the case will join a long list of unsolved acts of public art that lived a short life and left a longer argument.

For now, the image is already doing the work it was meant to do. People are debating whether proscribing a protest group and arresting hundreds at a rally is a proportionate response to political disruption. They’re arguing over whether defacing a court is a crime that speaks, or just a crime. And they’re wrestling with the uncomfortable idea that in a country that prizes free expression, the most pointed speech often appears where it isn’t allowed to be—and vanishes just as quickly.